In a series of posts giving a frank account of experiences on the NHS frontline, Sally Williams hears from Dr Jonathan Bennett, Honorary Professor of Respiratory Sciences, University of Leicester, Respiratory Consultant at Glenfield Hospital and Chair of the British Thoracic Society. Here’s what he said on 1St April 2020.

Coronavirus is forcing us to find completely different ways of working. When you’re thinking about COVID-19, the established approaches on the ward simply don’t apply. So, we need to work differently to meet the needs of patients, but also to protect healthcare workers by minimising their exposure to this highly infectious disease.

For example, as a respiratory physician, it’s hard to stop the compulsion to listen to a patient’s chest. However, we really shouldn’t be examining the patient’s chest with a stethoscope if we suspect they have coronavirus. It contaminates the stethoscope and it doesn’t have an impact on patient outcomes (it really doesn’t matter for the vast majority of patients with COVID-19 if there are extra chest noises).

Patient protocol

Patients with coronavirus are becoming instantly recognisable. Yesterday, there were 50 patients on the respiratory unit, of which 40 or so had the characteristic features of COVID-19. I didn’t see anyone who has presented as critically unwell with it, although they will need to be observed for several days in case they deteriorate. We have some patients in the ITU with coronavirus, but four patients I was worried about last week, because they required 60% oxygen and were for escalation to critical care, are thankfully getting better. We are still sending home a lot of patients at the front door.

In my unit we have developed a protocol specifically for patients we suspect of having COVID-19. First, we take a swab and sometimes a sputum sample.

- If the patient has the following, they are discharged home with advice: no shortness of breath at rest, with normal pulse oximetry (a test to measure oxygen saturation) at rest on room air, no adverse blood markers, minor chest x-ray changes and no social issues. The advice includes self-isolating for seven days, avoiding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (like ibuprofen), isolating the rest of the household, and calling 111 if needed.

- If the patient needs oxygen or has adverse markers or changes in their chest x-ray, we then make an escalation plan and admit them for at least 24 hours for observation. If they remain stable or improve, we discharge them home with advice.

- If the patient deteriorates, we use the HOPE strategy – Hydration, Oxygen, Paracetamol/Pneumonia management, and Early discharge or Escalation. We don’t routinely prescribe antibiotics. It’s a virus and the pattern of disease is pretty characteristic for many patients.

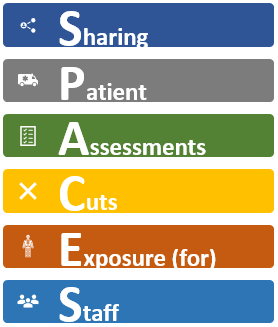

SPACES

We are also rethinking our approach to ward care. Traditional roles and working patterns don’t apply for a highly infectious disease. Usually, direct patient contact happens on multiple levels daily. The housekeeper goes to each patient bedside, provides drinks and food, does some cleaning, returns to remove food trays. A nurse will go to the patient bedside, conduct observations, provide medicines, and undertake other nursing duties. Allied health professionals may also see the patient. Separately, a doctor visits the bedside, chats with the patient and performs an examination. Each contact exposes healthcare workers or equipment to COVID-19.

To better coordinate care, we’ve introduced a new approach called SPACES: Sharing Patient Assessments Cuts Exposure for Staff. Any healthcare workers attending to a patient suspected or proven to have COVID-19 should do the following in one visit:

- Take in a new food tray and remove an old food tray

- Take and record the patient’s observations

- Ask the patient a set of specific questions to find out how they are

- Report that the patient has been seen

Where possible, staff should communicate with patients remotely. For example, ringing their bedside telephone or mobile and finding other ways to reduce face to face contact. It avoids the need for a series of people to change into PPE every time. Obviously, we won’t do this if it compromises a patient’s care or wellbeing. The aim is to avoid duplication of work and needless staff interactions with patients with COVID-19.

For me, it has meant asking patients if they want a cup of tea, taking in their lunch tray and recording the observations that nursing staff would normally do. Even at my age, I can learn that trick!

SPACES has the endorsement of the British Thoracic Society and the Royal College of Physicians. It’s not rocket science, but it means breaking ingrained work habits and may feel uncomfortable for many. But it should help to alleviate some of the extra high levels of anxiety we are seeing amongst healthcare workers. By minimising our exposure to COVID-19, we’re helping healthcare workers to focus on maximising outcomes for patients.

As told to Sally Williams